What the border carbon adjustment will mean for business – a primer

Introduction

Canada’s transition to net zero by 2050, which was enshrined in legislation in 2021, requires significant reductions of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. To achieve that objective, GHG emissions need to be included in our everyday business and consumption decisions. This is done by putting a price on emissions, expressed in carbon units, which has been implemented across Canada. The federal government intends to increase the price annually in the coming years.

While most industrialized countries are adopting carbon pricing mechanisms, our main trading partners have been less ambitious on the environmental front, relying on lower or no carbon pricing to date. Problems emerge when the prices of goods differ between jurisdictions due to the presence or absence of carbon pricing. We end up with less of an effective guarantee to reduce global GHG emissions and with newly created cost imbalances between trading partners.

Policymakers have come up with a way to “equalize” carbon prices called border carbon adjustments (BCAs). The European Union plans to begin phasing in BCAs, that they call Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanisms, in 2023, and Canada is undergoing consultations and reflecting on how to implement them. This report will:

- offer a high-level introduction on carbon pricing in Canada

- explain the importance of levelling carbon prices

- present border carbon adjustments (BCAs)

- discuss their implications for businesses and accountants.

Carbon Pricing in Canada

Canada has implemented a flexible approach to carbon pricing in which provinces and territories can design their own pricing system provided they meet the federal minimum benchmark. The pricing systems implemented in Canada cover emissions from fuels and emissions from large industrial emitters with either carbon taxes or trading systems.

Trading systems for industries are either output-based pricing systems or cap and trade systems. The former relies on a fixed carbon price while the latter relies on a fixed level of total emissions. Within these systems, large emitters or fuel suppliers must offset their emissions and can do so by buying or selling emissions credits depending on their environmental performance. By design, these trading systems generally have built-in levels of emissions for which industries do not have to pay (i.e. free or exempt emissions) that might differ across jurisdictions.

This flexible approach has led to a complex carbon pricing environment in Canada regarding the choice of pricing system and the jurisdictional coverage.

- Some provinces and territories have unique carbon taxes, others have cap and trade systems and the remainder have fuel carbon taxes with output-based pricing systems.

- Some provinces rely entirely on their provincial or territorial system, some rely partially on the federal backstop (either for fuel carbon taxes or output-based pricing system) and some rely entirely on the federal backstop.

Transitioning toward a more sustainable economy relies on sending a stronger price signal to consumers and industries in the coming years. Canada has committed to increasing carbon prices by $15 per tonne every year until 2030, more than tripling the carbon price between 2022 ($50) and 2030 ($180). These increases will trickle across Canada as provinces and territories must meet the federal minimum benchmark.

In a report, Environment and Climate Change Canada estimated that the pricing systems in Canada theoretically cover 91 per cent of total emissions. However, the exemptions within pricing systems total 13 per cent of Canada’s emissions: two per cent associated with fossil fuels and 11 per cent with industries.

This report will focus on carbon pricing for industries rather than fossil fuels carbon taxes. The financial implications of industrial carbon prices are concentrated on large facilities and can impact their ability to compete on global markets. In comparison, fuel carbon taxes are spread out among all Canadian consumers and businesses.

A Level Playing Field for Businesses

As mentioned earlier, Canada is not alone in implementing carbon pricing. The World Bank estimated that more than 40 countries had implemented or were considering implementing carbon pricing mechanisms. Industrialized countries account for most of the pricing jurisdictions. Most notably, the European Union has implemented carbon pricing through a cap-and-trade system between member countries. As for the United States, there is no federal carbon pricing in sight, but several states have implemented cap and trade systems.

A host of diverging carbon prices become problematic when you factor in the importance of trade. Canada’s trade volume is equivalent to 60 per cent of our GDP, several percentage points higher than the world’s average of 52 per cent. Trade data for 2021 indicated that most of Canada’s trading is with partners that have lower or no carbon prices. A quick look at our imports highlights the importance of the United States and China among these trading partners.

On the environmental front, less stringent or lack of carbon pricing among our trading partners is detrimental to global emissions reduction targets. Lower carbon price jurisdictions could attract emitting industries and Canadian businesses could choose to expand or relocate their activities in these countries. The potential increases in carbon emissions by Canadian businesses in other countries are called carbon leakages and can in effect offset the reduction of emissions within Canada. Furthermore, less stringent countries can also directly impact our effort to reduce emissions since current exemptions to industrial carbon pricing are mainly put in place to protect our industries’ competitiveness in global markets.

By creating an imbalance in operating costs between jurisdictions, diverging carbon prices also have their share of economic and financial implications. Higher operating costs in Canada can lead to smaller profit margins and higher-priced goods, resulting in less competitive domestic products in domestic or foreign markets. This in turn impacts our capacity to export, grow and even attract business in emitting industries. With Canada’s economy relying on the country’s endowment in natural resources, our ability to compete in global commodity markets is of high importance.

Those consequences of diverging carbon pricing are well known and have been discussed in detail. So much so that the International Monetary Fund is trying to establish a global carbon price floor for large emitters. Canada would probably still need to level the playing field regarding carbon prices because it is unlikely that an international price floor would be on par with Canada’s rapid price growth. If anything, an international price floor would make it easier to adjust carbon prices with our trading partners as the upward carbon price adjustment would always be starting from the floor price.

Introducing Border Carbon Adjustments

Policymakers have come up with a trade policy option that adjusts for differences in carbon prices between trading partners called border carbon adjustments (BCAs). In essence, BCAs ensure that domestic and foreign goods producers pay the same carbon price when they are competing, i.e., selling their goods, on the same domestic or foreign market. It can do so by charging import fees for goods produced in lower-carbon priced jurisdictions or by subsidizing exports (export rebate) that have paid a higher domestic carbon price. As with most trade policies, the complexity lies within the specifics and many decisions regarding BCA design will need to be taken, notably on:

- Trade coverage: BCAs can apply fees to importing goods entering Canada (import fee). BCAs can also subsidize Canadian exports (export rebate) to countries with lower carbon price.

- Emission scope: BCAs can cover direct emissions associated to the production of goods (scope 1), indirect emissions from the generation of the energy used to produce goods (scope 2) as well as all other indirect supply-related emissions (scope 3).

- Geographic coverage: BCAs could be applied to all trading partners or could offer differential treatment for developing countries.

- Sectoral coverage: BCAs could initially apply to emissions-intensive and trade-exposed sectors or could extend to all sectors importing or exporting goods.

- Embedded emissions: Emissions required to bring a good to market (embedded emissions) could be estimated with sector or good-specific benchmarks or could be calculated by producers.

- Equivalency: BCAs could adjust for different environmental policies. Adjusting for diverging carbon prices would be the simplest, meanwhile adjusting for non-pricing environmental policies (such as environmental regulations impacting the cost of production) would be more complicated.

- Revenue use: BCA revenues from import fees can be kept in Canada, used for environmental purposes, recycled into export rebates, or simply go into Canada’s consolidated revenue fund. They could be sent abroad to help developing economies reach their environmental goals.

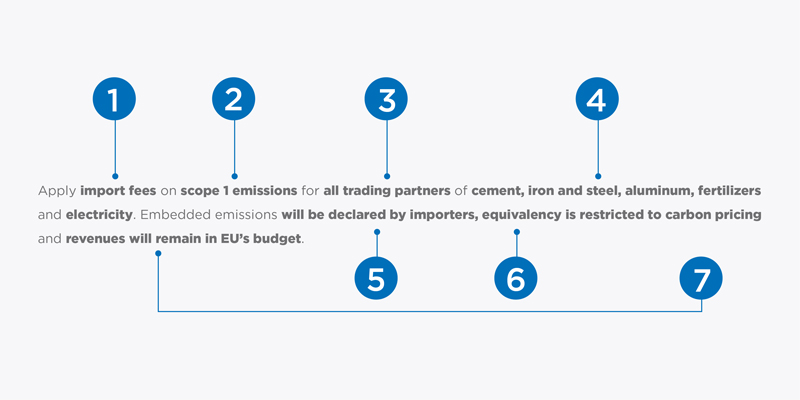

The federal government initially announced, in Budget 2021, its interest in implementing BCAs across Canada. They are currently undergoing consultations with Canadians while pursing discussions with our trading partners, the United States being the key one. Europe is the farthest along with legislation to implement BCAs through an extension of the European cap-and-trade scheme to importers. They will be phasing in BCAs implementation with reporting starting in 2023 and carbon adjustments being paid from 2026 and onward. The following illustration highlights their decisions regarding BCA design.

Europe's BCA design

To further expand our understanding of BCAs, the following table presents a simple representation of carbon adjustments for Canadian and American businesses active in both markets. For the sake of the example, carbon pricing is set higher in Canada and emissions intensity is set lower. This results in a higher carbon price paid by Canadian businesses operating in Canada ($400) and a carbon price that would be lower if they operated in the United States ($300). As for the American businesses, they pay $375 per unit sold on the domestic market and it would cost $500 per unit if they operated in Canada. Assuming the border adjustment applies in both jurisdictions for imports and for exports, and accounts for carbon price paid domestically:

- Businesses operating in Canada and exporting to the US would have to be financed by a rebate of $100 per unit to account for a higher carbon price paid in Canada.

- Businesses operating in the US and exporting to Canada would have to pay a fee of $125 per unit to account for the higher carbon price paid in Canada.

Since BCAs are trade policies, they will interact with the World Trade Organization (WTO) agreements. It is particularly important for Canada to implement BCAs carefully because of our intricate trading relationship with the United States. The International Institute for Sustainable Development studied BCA compliance with WTO law and concluded that Canada should focus on import fees. Applying the domestic price on carbon for imports would be less problematic than subsidizing exports through rebates. In addition, they mentioned that equivalency between domestic and foreign environmental policy should stick to carbon pricing only.

Ultimately, the risk of protectionist pushback could be reduced with adequate cooperation and collaboration with our trading partners. The Canadian Climate Institute mentioned that coordinated action could increase administrative efficiency and maximize the upside of BCAs. In that regard, the concept of a Climate Club, essentially a group of countries applying similar carbon pricing which would extend their pricing to countries they trade with, has been discussed. Climate club could potentially reduce the cost of implementing BCA for participating countries meanwhile putting more coordinated pressure on non-participating countries.

Implications for Businesses and Accountants

When a new policy tool is brought forth, the question generally is: what will it mean for my business and ultimately my job? On the business front, we can initially expect the introduction of import fees to impact trading activities. Carbon prices will be signaled across companies’ supply chains essentially erasing competitive advantages resulting from less stringent environmental policies.

- For businesses operating in higher carbon price jurisdictions (HCPJ), they will have to expect a higher price for imported goods from suppliers operating in lower carbon price jurisdictions (LCPJ). In turn, this would make goods produced in HCPJ more competitive and could lead to supply chain consolidation within countries or with HCPJ trading partners.

- For businesses in LCPJ, exporting into HCPJ will become costlier. They will transfer the additional cost of doing business to their clients, ultimately impacting their competitiveness.

Factoring in carbon prices in trading activities will ultimately lead to companies reducing their emissions intensity across jurisdictions. Since access to foreign markets will be subject to higher carbon pricing, companies will be incentivized to reduce their emissions to pay lower import fees, thus improving environmental competitiveness. As carbon prices rise over time, accessing HCPJ will further depend on a business’s capacity to curb its emissions.

BCA implementation will imply additional reporting for businesses. In Europe, the first three years of implementation (2023-2026) will focus exclusively on setting up the reporting ecosystem. Importers will be asked to report quarterly on imported goods, embedded emissions and carbon price paid per covered good and import source. Additionally, submitted import and emissions information will have to be verified by a third party, and could be subject to audit from regulating agencies. As BCA gets implemented in or outside of Canada, we could see firms operating in Canada on both sides of the reporting requirements as importers or as firms accessing the European market.

The accountancy profession has an important role to play to ensure that these new policies effectively drive organizations towards lower carbon business models. For example:

- Accountants within organizations may be responsible for determining appropriate accounting for BCAs and assessing financial and tax implications of BCAs.

- Within organizations, accountants will adapt business strategy, supply chains and investment plans regarding the implications of BCAs.

- Audit practitioners will be looked to for assurance over emissions to enhance credibility of reported emissions.

As momentum around sustainability and climate action continues to grow and policy and regulation around sustainability initiatives evolve, accountants will be called upon to incorporate policy considerations into business strategies, consider the financial impact of climate risks, tax implications, and provide assurance.

It is critical for accountants to monitor policy developments related to carbon pricing that will impact their organizations and clients.