Would you implant a microchip in your hand?

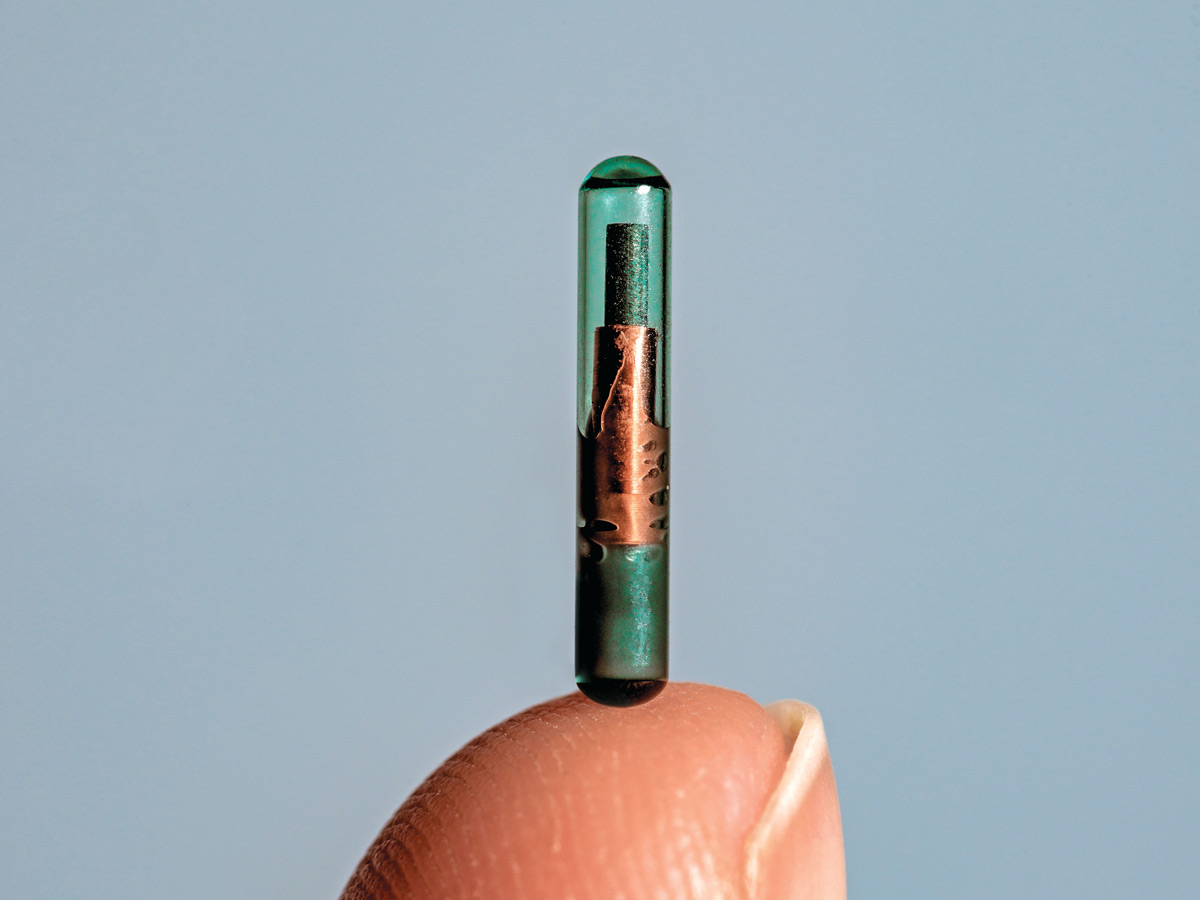

VivoKey’s Implantable chips start at US$49 and are about the size of two grains of rice (Daniel Neuhaus)

VivoKey’s Implantable chips start at US$49 and are about the size of two grains of rice (Daniel Neuhaus)

Amal Graafstra never carries house keys. Instead, he has a microchip in his hand that automatically unlocks the front door of his Seattle home. It also auto-fills log-in pages on designated websites. All he has to do is get close enough to his house or laptop and the chip—which is embedded with radio frequency identification (RFID) technology, similar to what makes a tap credit card work—does the rest.

Such cyborg-ian body modifications have been around for at least 15 years; Graafstra got his first in 2005. But until recently, they appealed strictly to daring early adopters with the technological know-how. According to the popular tech website Ars Technica, an estimated 50,000 to 100,000 people worldwide have implants.

Graafstra is hoping to broaden the market. In 2009, through his company VivoKey Technologies, he started selling chips like his own online. They’re the size of two grains of rice and cost between US$49 and US$129 each. A willing doctor or piercing specialist can inject them, most often into the soft tissue between the thumb and pointer finger. Since 2014, Graafstra has seen more than 700 per cent growth in sales. “The first couple of years,” he says, “I went from zero to selling thousands of implants around the world.”

As many as 100,000 people worldwide have tech implanted in their bodies

But not everyone is lining up to get chipped. By and large, consumers are still wary of the potential medical, ethical and security risks, like malfunctions or being tracked or hacked. VivoKey implants, at least, can’t be tracked by GPS and feature encryption that protects from malware.

Nikolas Badminton, a Toronto-based business consultant who advises executives on the future of technology and innovation, has a VivoKey chip in his hand, and he can imagine a day when getting an implant “will be as normal as getting a tattoo.” For now, he says, medical applications—such as a glucose-monitoring implant for people with diabetes—will be more culturally acceptable than non-essential implants. Elon Musk might agree. His recent startup Neuralink is attempting to create implants that allow paralyzed people to control their phones and laptops through brain waves alone.

VivoKey’s more immediate competitors include Sweden’s Biohax, which has sold more than 4,000 implants in its home country, enough that the national train line installed RFID readers to scan e-tickets stored on subdermal chips. It may be a sign of things to come. “Eyeglasses, wristwatches, headphones—they’re all examples” of the ways we use new technologies to change our bodies, says Badminton. “Implants are just a little more permanent.”