Why Quebec is betting big on Bitcoin

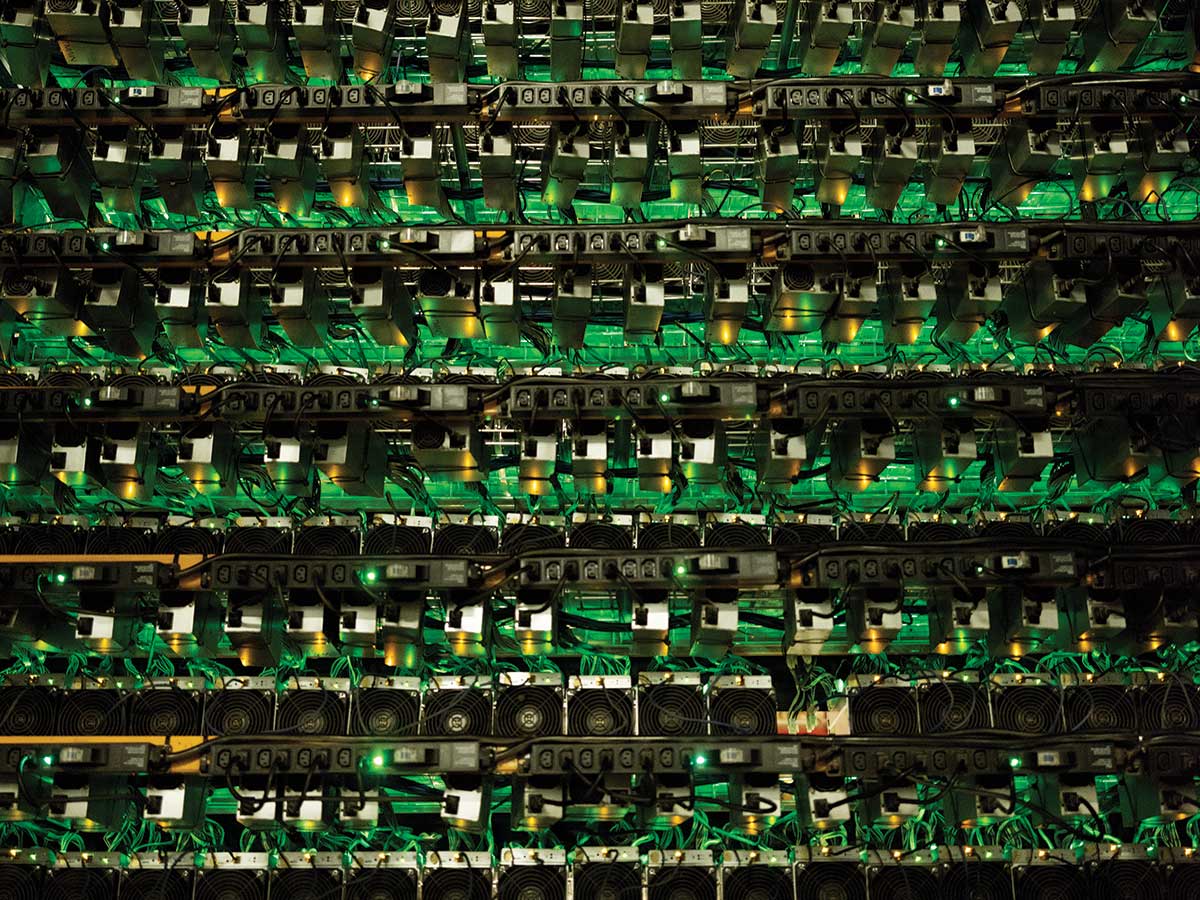

Saint-Hyacinth, one of several small Quebec cities with a Bitfarms mining facility (Guillaume Simoneau)

Saint-Hyacinth, one of several small Quebec cities with a Bitfarms mining facility (Guillaume Simoneau)

In places like Saint-Hyacinthe, Quebec, in the bowels of long-abandoned warehouses, there is the sound of money being made.

Generated by thousands of four-inch fans turning clockwise in unison, it’s akin to a constant swarm of bees. This literal wall of sound is looped with wires and pulsing with green lights—some near-future set piece plunked into the industrial scrapes of a Montreal exurb.

The noise and heat—the room feels like a Florida tarmac—is the by-product of 6,500 computers. Each one is roughly the size of a loaf of bread and is doing the same thing as its many neighbours: cracking mathematical equations. When an equation is solved, the computer is rewarded with Bitcoins, the world’s reigning cryptocurrency. It then moves on to another equation. Then another.

All told, an operation like the one in Saint-Hyacinthe will harvest an average of 3.5 Bitcoins a day, which in the rodeo-esque world of Bitcoin trading is worth anywhere from about $2,200 (in early 2016) to roughly $88,500 (in late 2017) or somewhere in between ($18,300 this past November). Call it a noisy cog in the wheel of the digital economy, in which computing power mates with copious amounts of electricity to churn out a currency that exists only in an ethereal ledger.

The Saint-Hyacinthe warehouse is one of five such facilities that Bitfarms, one of the largest Bitcoin mining firms in the country, has built since 2017. It’s also a model of how the company plans to make Quebec a global Bitcoin harvesting centre. Bitfarms, which is listed on Israel’s Tel Aviv Stock Exchange, had revenues of US$22 million in the first half of 2018, according to its financial statements. It has plans for another three facilities, for a total of 162.5 megawatts of power consumption. That’s enough to mine hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of Bitcoin a day—or to power more than 120,000 homes.

Globally, Bitcoin mining will soon consume nearly as much energy as the entire country of Austria uses in a year, according to a recent report published in the energy research journal Joule. Another study, in Nature Climate Change, claims Bitcoin mining could singlehandedly increase global temperatures by two degrees Celsius, the limit set in the Paris Agreement, within 30 years.

Globally, Bitcoin mining will soon consume as much energy as Austria uses in a year

Bitfarms is not the only game in town. Over the last several years, Bitcoin miners from around the world have set their sights on Quebec for one simple reason: cheap, abundant and comparatively green electricity, sourced from the province’s myriad hydroelectric operations. The province was happy to trade its excess power for a chance to get in on a high-tech phenomenon—for a while, at least.

By May 2018, the rush of would-be miners proved so great that the provincial government ceased issuing new electricity contracts. From the fall of 2017 until the moratorium, 300 cryptocurrency mining and blockchain outfits petitioned Hydro-Québec, the province’s public utility, for some 18,000 megawatts of power. By comparison, Quebec’s well-established aluminum industry buys about 2,700 megawatts from Hydro-Québec.

The worry, telegraphed both by Hydro-Québec and former premier Philippe Couillard, is that these automation-heavy operations won’t provide much in the way of jobs, but will overload even Quebec’s formidable electrical capacity and expose the province’s economy to Bitcoin’s boom-and-bust spikes. “If the market were to tank, most for-profit miners would no longer be able to offset their costs and would likely exit the market,” says Jeremy Clark, a professor and cryptocurrency expert at Concordia University.

Another problem is the gold-rush-like atmosphere surrounding Bitcoin. There is a finite number of Bitcoins, and the algorithms to mine them are designed to become exponentially more complex as more computers try to solve them. Governments worry that Bitcoin miners, much like prospectors of yore, will begin disappearing as harvesting becomes more cash- and energy-intensive—and disappear outright when there are no more Bitcoins to be had.

“Though we have certain energy surpluses, we simply can’t connect every would-be Bitcoin farmer who knocks on our door,” said Hydro-Québec spokesperson Jonathan Côté. “If we were sure these demands were going to be here in five or 10 years, we might be able to up capacity. But that certainly isn’t the case.”

Bitfarms says it is different than the fly-by-night Bitcoin miners. Instead of just reaping Bitcoins, Bitfarms co-founder and president Pierre-Luc Quimper wants to use the blockchain, Bitcoin’s underlying virtual ledger, as a backbone to host authentication, logistics and payment systems for companies and individuals. The blockchain’s open-source ubiquity and transparency, along with its robust security, provides an ideal arena for financial transactions between companies. In other words, mining Bitcoin is just a lucrative opening act. Bitfarms’s true future, Quimper believes, lies in the blockchain.

Just a few of the 6,500 mining computers at Bitfarms’s Saint-Hyacinthe operation (Guillaume Simoneau)

Just a few of the 6,500 mining computers at Bitfarms’s Saint-Hyacinthe operation (Guillaume Simoneau)

Big businesses are on the same wavelength. Two years ago, Walmart and IBM partnered to create a blockchain project that monitors food safety for the Arkansas-based retail giant. Maersk has a blockchain project to monitor shipping. De Beers has done the same to track the sale, importation and authenticity of its diamonds.

Quimper wants to use his company’s computer prowess to mine Bitcoin, using the proceeds to first expand its facilities and then leverage its digital footprint to get into the world of logistics and financial transactions—a far more lucrative market in the long run, he believes. To this end, Bitfarms has partnered with Montreal engineering school École de technologie supérieure on a blockchain research project, with the goal of sussing out practical applications for the technology beyond cryptocurrency.

“Two years ago, when I saw everyone was getting into Bitcoin and flooding the market, I saw the way to make money was through infrastructure,” says Quimper. “I want a company like Air Canada to come to us. We’ll do the ticketing, we’ll do the logistics, we’ll do the algorithms, we’ll do the infrastructure all on blockchain. The real money is in what’s coming.”

Bitcoin came to life in 2009 thanks to a person or group known as Satoshi Nakamoto, ostensibly a Japanese software engineer whose true identity remains unknown. Though its founder is nebulous, Bitcoin was a definitive solution to an enduring problem for digital ideologues: how to perform decentralized financial transactions securely and (relatively) anonymously over the internet.

More than 17 million Bitcoins have gone into circulation since 2009, the transactions of which are permanently recorded on a giant ledger known as the blockchain. About every 10 minutes, the Bitcoin network releases a new block to the chain containing all the transactions since the last block. Mining this new block requires computers to solve mathematical problems—or, more accurately, guess at the answer several trillion times a second. The computer that guesses correctly first gets a set amount of newly minted Bitcoins (12.5, currently). Bitfarms’s existing facilities, totalling 27.5 megawatts of power, mine an average of 9.275 coins a day, the value of which fluctuates wildly every day.

Nakamoto limited the total number of Bitcoins to 21 million (most estimates suggest they’ll all be mined by 2140). And the more computers mining Bitcoin, the harder it is to actually obtain them—the difficulty of the process is relative to how much computing power is on the network at any given time. In turn, that means miners require ever more electricity. As a result, Bitcoin miners have flocked to Iceland, Sweden and parts of the United States where power is relatively cheap. In 2017, they came calling on Quebec.

To be sure, the province has long been a destination of choice for power-hungry industries. In 1901, the country’s nascent aluminum industry settled in Quebec, lured by the cheap power flowing from Shawinigan Falls, about 160 kilometres northeast of Montreal.

As hydroelectric plants popped up on the Quebec landscape, so too did aluminum smelters. Today, nine of 10 major Canadian smelters are located in the province. Cement factories are prolific in Quebec as well, as are data centres and clandestine marijuana grow houses. Though these products serve different markets and proclivities, they have one thing in common: they wouldn’t exist without the province’s cheap and plentiful power.

Blockchain, not Bitcoin, is the future, says Quimper. “We’re at the beginning of something huge.”

In the summer of 2016, as part of a plan to double revenues over the next 15 years, Hydro-Québec launched an initiative to woo more data centres to the province. As charm offensives go, it was all carrot, not much stick. It included access to government assistance programs, a 25-million-square-foot array of available real estate, IT support and rates as low as four cents per kilowatt hour. (By comparison, the lowest off-peak commercial rate in Ontario is 6.5 cents.)

The offer attracted data centres and Bitcoin miners alike. The Chinese firm Bitmain, which also manufacturers the industry-leading Antminer computers used in most of the world’s cryptocurrency mining operations (the Antminer S9 performs between 13 and 14.5 trillion guesses per second), met with Hydro-Québec in 2018. David Vincent, the utility’s business development director, has said that “three or four” of the world’s biggest blockchain players have sniffed around for a spot in Quebec to plug in.

All told, some 300 companies of varying sizes presented plans to Hydro-Québec, according to Côté. The utility accepted 20 proposals before it introduced a moratorium on further requests in June, and began penalizing mining companies that defied the moratorium—by, for example, pretending to be a greenhouse—by charging them a penalty rate of 15 cents per kilowatt hour.

“It was just too much,” says Côté of the demand. “Even if we just went with the ‘serious’ requests, the ones with proper business plans and whatnot, we’d need to outlay up to 6,000 megawatts. That’s four times the surplus capacity we have available for all industries. We don’t want to make all that capacity available exclusively to the cryptocurrency and blockchain industries.”

Bitfarms’s advantage was its early arrival to market. The company’s first mining operation came online in July 2017 before the Bitcoin rush, in a small village about 70 kilometres southeast of Montreal. In April, it merged with Israel-based Blockchain Mining Ltd. The company secured contracts for all its energy demands before the moratorium. In fact, admits Bitfarms CEO Wes Fulford, the moratorium actually helped Bitfarms by closing the market to further potential competitors.

Bitfarms president Pierre-Luc Quimper (Guillaume Simoneau)

Bitfarms president Pierre-Luc Quimper (Guillaume Simoneau)

Bitfarms got in early because of Pierre-Luc Quimper. A native of New Brunswick who somehow convinced his parents to let him drop out of school in Grade 5, Quimper opened his first company, a web hosting outfit called GloboTech Communications, in 1999. At first, Bitcoin was a way to pay the mortgage.

“I bought a house and wanted a way to stay there for free, so I bought a bunch of servers,” the diminutive Quimper says from behind the wheel of his Lamborghini Aventador—an extravagance that GloboTech’s success, not Bitfarms, afforded him. “After about three months, I didn’t want to sleep there because it was so bloody hot and the electrical panel was constantly about to blow up.”

Lamborghini notwithstanding, Quimper looks the part of an indifferent millionaire. He usually shows up to work unshaven, in baggy jeans and a Bitfarms golf shirt, peering from behind thick glasses. He is also a PR person’s nightmare, particularly behind the wheel of his Aventador. Exactly why Quebec’s public electricity utility won’t give him more power is a frequent source of his ire. “Hydro-Québec wants to up the price for this one industry,” he tells me as we weave through traffic on Autoroute 20 between Montreal and Saint-Hyacinthe. “It’s a mistake. Look at data centres. At first, Hydro-Québec didn’t want them here. Now they give them special prices, and we have huge data centres here as a result. It’s why Amazon is coming here. We’re long-term. We want the same thing.”

Along with electricity, Bitcoin mining requires industrial space with ready access to the electrical grid. Quimper and his partners found all three in places like Saint-Hyacinthe, Cowansville and Sherbrooke—towns and cities whose industrial bases have fallen on hard times. The Saint-Hyacinthe facility is housed in a former cocoa storage warehouse. The Farnham plant, where today some 6,700 mining computers hum along, used to manufacture carpets. Thetford Mines and Baie-Comeau, two other formerly grand industrial towns, have expressed interest in hosting Bitfarms.

Along with cheap rent and proximity to the grid, these towns usually draw an excess of power that would otherwise go unused. “We sat down with the head of Hydro-Québec and picked spots where there were surpluses,” Quimper says. That optimizes costs. It also has the effect—intended or not—of helping them escape the criticism of environmentalists who would argue their mining operations are a burden on the planet.

“We simply can’t connect every would-be Bitcoin farmer who knocks on our door.”

Bitfarms has supporters in those spots as a result. Last May, Sherbrooke Innopole director general Josée Fortin wrote a letter to Quimper “strongly supporting the Bitfarms project, which answers several of the needs of the changing Sherbrooke economy.” For cities like Sherbrooke, which own their own electrical distribution network, Bitfarms presents a tempting offer indeed: the company doesn’t ask for tax breaks, pays for its own infrastructure, and buys power that would otherwise go unused.

Yet others, while happy with Bitfarms’s proposition, have yet to see the rewards. Both Bitfarms and competitor BitLinksys secured contracts with Magog, a largely tourism-based town in Quebec’s Eastern Townships. BitLinksys said it would be online by June; by November, it had yet to mine any coin. Bitfarms isn’t online yet either.

“It’s not as frustrating as it is astonishing,” says Magog mayor Vicki-May Hamm of the delays. “It seemed really important that we sign and get them the electricity quota as fast as possible. Unfortunately, neither company has begun mining, and we aren’t selling any electricity. And a town that doesn’t sell electricity doesn’t make any profit. We wanted those profits sooner to reinvest in our infrastructure.” (Bitfarms says the infrastructure in its Magog plant is in place, and that the company is currently deciding what kind of Bitcoin mining hardware to purchase.)

Another issue is jobs. Bitcoin mining, being a largely automated endeavour, isn’t a huge job creator. According to a KPMG report published in 2018 for Hydro-Québec, a 20 megawatt cryptocurrency mining operation generates 1.2 jobs per megawatt. Bitfarms, for instance, has about 100 employees. By comparison, a dedicated data centre creates five, while an actual bricks-and-mortar mine creates 27. “The economic impacts of Bitcoin mining are much less per unit of energy than of a data centre of comparable size,” reads the report.

Yet the same report is comparatively bullish on the “promising future” of the blockchain’s economic potential as a business platform. The blockchain is essentially an online ledger that records transactions. Anyone can make and record a transaction—so long as there’s consensus from all participants. As such, it can take the place of third parties who would otherwise be trusted with overseeing transactions between individuals and companies.

“Essentially, we’re shifting responsibilities of trust from humans and organizations to technology,” says Kaiwen Zhang, a professor and blockchain expert at Montreal’s École de technologie supérieure.

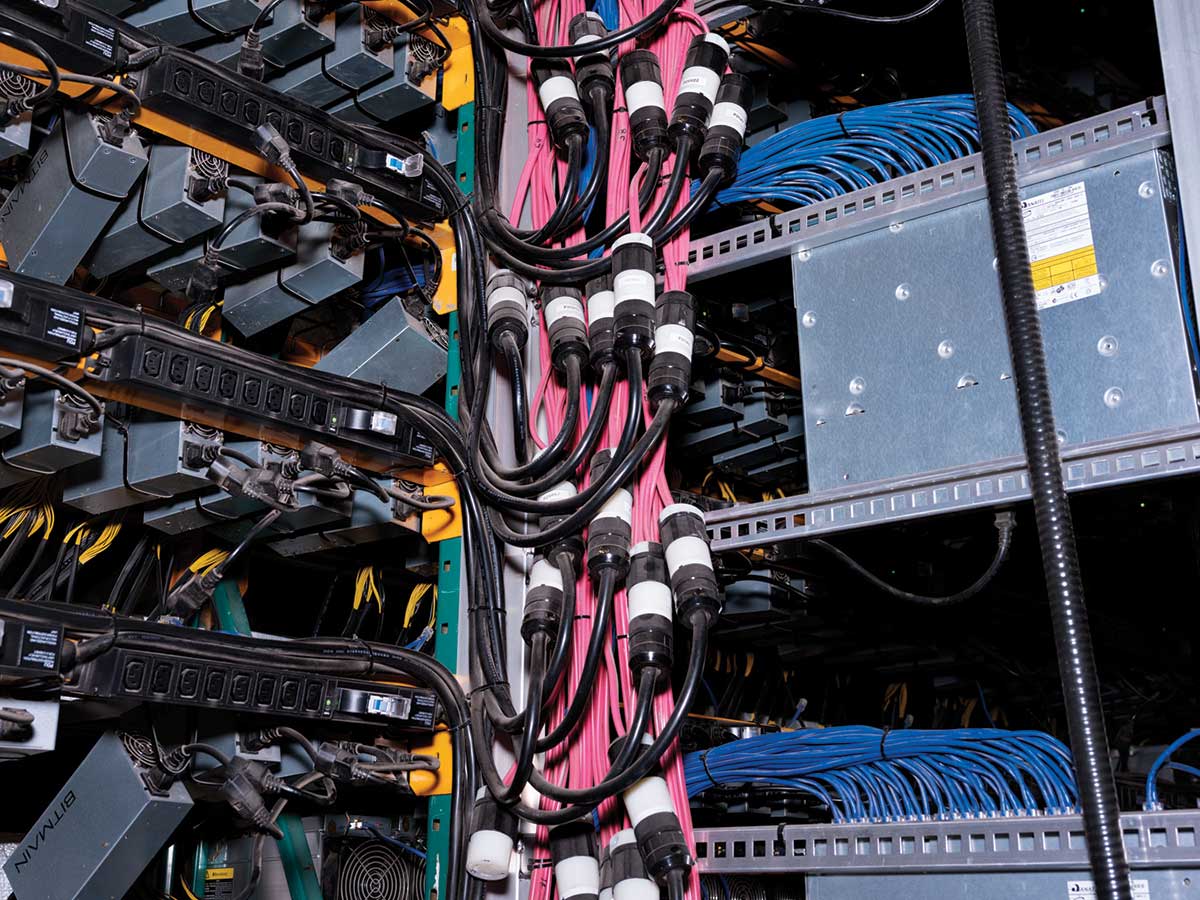

Along with electricity, Bitcoin mining requires industrial space with ready access to the electrical grid (Guillaume Simoneau)

Along with electricity, Bitcoin mining requires industrial space with ready access to the electrical grid (Guillaume Simoneau)

The implications of blockchain-based applications are considerable. For example, blockchain-based real estate transactions would enable buyers and sellers, two entities who don’t necessarily trust one another, to negotiate price, set conditions and complete a sale without a third party. By the same token, the blockchain could arguably take the place of many banking and financial services.

“The blockchain is a trustless system,” says Louis Roy, a chartered professional accountant and blockchain leader at Catallaxy, the blockchain consulting arm of Raymond Chabot Grant Thornton. “It allows you to do business with someone who you don’t completely trust.”

The blockchain is also uniquely suited to logistics. In the case of Maersk, which launched a blockchain-based shipping platform in collaboration with IBM earlier this year, it has allowed the Danish shipping giant to track various shipping “events”—departure, customs information, bills of lading—in real time, without relying on antiquated computer systems or paper-based legal documents that currently dominate the industry.

According to an International Data Corporation report published in July, worldwide spending on blockchain solutions will rise to US$11.7 billion in 2022 from the US$946 million spent in 2017.

“The potential market size is enormous,” says Roy. “Talking about registries isn’t sexy. But in life pretty much everything we do is part of a registry. And fundamentally what is the blockchain? It is a decentralized registry. Financial transactions are recorded in a register. The government has personal information on you and me; all of it is in a registry. And decentralizing registries is what makes them more secure.”

Blockchain applications are very much in their infancy. Yet as the number of Bitcoins diminish and become more difficult (and expensive) to mine, companies relying on myriad Bitcoin mining machines pulling money out of the ether won’t likely last long. For Pierre-Luc Quimper, the future of Bitfarms lies not in Bitcoin but the infrastructure supporting it.

Currently, Bitfarms mines Bitcoins. Yet Quimper wants to transition the company to something bigger, in part due to the difficulty and volatility of Bitcoin mining. It will instead use the blockchain technology behind the cryptocurrency as a secure, virtually un-hackable and fully traceable framework on which companies can set up their logistics and inventory systems. According to Quimper, Bitfarms can both design and host these systems in the future using its existing infrastructure. He says Bitfarms’s transition from Bitcoin miner to blockchain host will mean more jobs and less susceptibility to Bitcoin’s rodeo-like swings in value.

“We are at the beginning of something huge,” he says. “We want to be a vertically integrated company that finances its future by mining Bitcoin. Blockchain applications are cheaper, more secure and more adaptable than anything that exists now. Bitfarms will be integral in blockchain solutions. We don’t want to just consume electricity.”