How a family business can make big money—and drama

HBO’s Succession shows how a family business can tear at the fabric of the family itself (Photography by Peter Kramer/HBO)

HBO’s Succession shows how a family business can tear at the fabric of the family itself (Photography by Peter Kramer/HBO)

Tell me if you’ve seen this show before.

The high-living, silver-maned patriarch of a global enterprise, with billions in revenues and diverse holdings around the world, builds a corporate powerhouse from scratch, expands into risky side ventures and makes strange digressions into politics. The prodigal daughter, in turn, spends time in the trenches of politics, but eventually returns to the business. Tensions surface. A supporting cast of siblings, relatives, investors and consiglieri orbit what becomes a Lear-like drama, which starts out promisingly enough (as they all do), but takes a decidedly a Wagnerian turn, featuring epic battles waged in court by legal emissaries, in full view of the vultures of the business press.

Not Rogers.

Nor the addictively realistic feuding of Logan Roy’s clan in HBO's Succession.

This drama, rather, involves the on-again-off-again infighting that continues to rip through the family behind the Magna International auto-parts empire, founded in the late 1950s by Frank Stronach—a hard-driving, opinionated tool and die maker who decamped from post-war Austria to Canada, where he rode the wave of North America’s unending affection for cars.

Magna and Linamar, a Guelph, Ont.-based manufacturer, seemed to travel on parallel trajectories. Linamar was established by Frank Hasenfratz, a Hungarian refugee, in 1966. It, too, became a major player in Canada’s auto-parts sector. In 2002, Hasenfratz turned over the reins to his daughter, Linda, and she went on to build Linamar into a firm, which, in 2020, had $5.8 billion in sales.

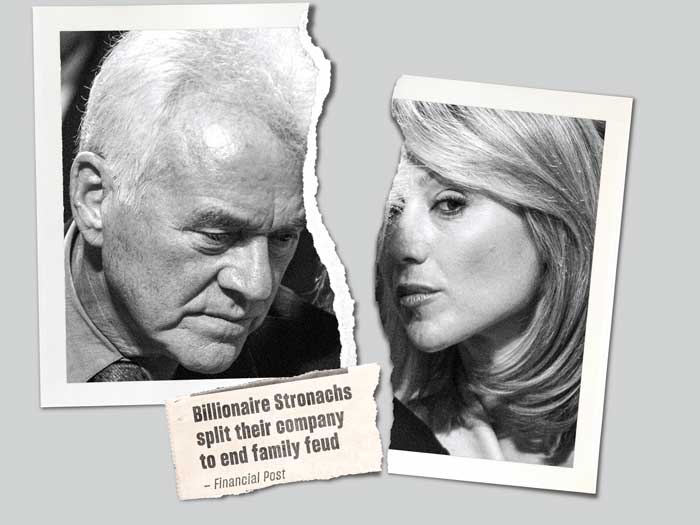

A year earlier, Frank Stronach had handed the operations of Magna to his daughter Belinda, who soon took a prolonged leave to spend a few years as a Liberal MP in Ottawa. Through a complex series of transactions, the family in 2010 divested control of Magna, with Frank and Belinda turning their attention to Magna’s horse-racing and gaming interests. Leaving his daughter in charge, Frank returned to Austria to run a political party. But, in 2018, Frank and his wife Elfriede sued Belinda, her children and a former business associate for $500 million, claiming mismanagement. After two years of legal sparring, father and daughter patched things up, but lawsuits have continued to fly. The current cast of litigants features the Stronach’s son Andrew, who took legal action against his sister Belinda and others for breach of fiduciary duty in relation to the tangle of trusts that hold the wealth that Magna's plants generated over decades. Season three shows no sign of ending.

Magna CEO Belinda Stronach (right) and her father Frank (Getty)

Magna CEO Belinda Stronach (right) and her father Frank (Getty)

The history of Canadian capitalism is punctuated by these kinds of spectacular family fights and meltdowns, most of which involve the frequently contentious matter of transitioning business empires from one generation to the next. The list takes in some of Canada's most prominent clans including McCain (McCain Foods) and Billes (Canadian Tire), as well as others for whom inter-generational transitions were less fractious or at least more discreetly handled, including empires built by the Irvings (Irving Oil), the Desmarais family (Power Corp.), Bronfmans (Seagrams/Edper) and Shaws (Shaw Communications). Many feature the Shakespearean elements of feuding siblings, parental favouritism, greed and the seemingly inevitable loss of original entrepreneurial ferocity that has brought about the demise of many once-great business dynasties.

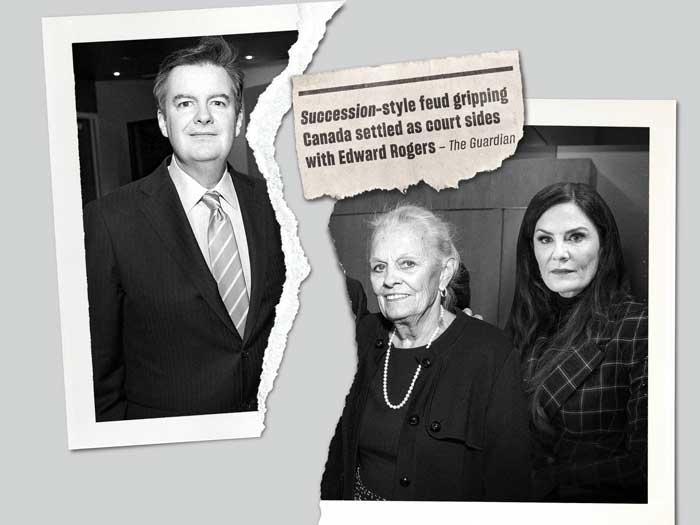

While these dramas are not new, last year’s social media-fueled showdown inside the Rogers family and its controlling trust, in the midst of a $26 billion takeover of the Shaw family’s communications company, provided an exceptionally salacious variation on the theme. That drama began with an attempt by Edward Rogers III to oust the CEO, which rapidly became a highly visible fight starring two warring camps of the Rogers family, a collection of Ted’s long-standing Bay Street pals and a family trust that held more cards than most people realized. Public interest in such conflicts has been further amplified by the huge success of the HBO series, which features Brian Cox and Jeremy Strong, and follows the vicious intrigues in a fictitious billionaire family that could be a mash-up of the Trump and Murdoch clans.

The combination of the series and the Rogers’ battle has put the issue of transition back on the radar of a lot of family-owned firms, or at least moved it to the front burner. Both reaffirmed how these kinds of melodramas are entirely plausible.

Yet Michelle Osry, a CPA who leads Deloitte Canada’s family enterprise practice, feels that high profile conflicts tend to distort the reality of most family business transitions. “We believe that there has been considerable focus on the tragedies of enterprising families as compared to the triumphs,” she says. “We could point to thousands of success stories. Unfortunately, media and some advisers tend to promote and perpetuate fear-based planning.”

Other experts point out that one key sub-plot of the Rogers’ fight—the company’s use of dual-class shares as a means of retaining family control over a publicly traded company —has shone a new light on a capital structure practice that has fallen into disrepute among governance experts and institutional investors in recent years. “After Rogers, the talk about dual class shares has really picked up,” says Aida Sijamic Wahid, an associate professor of accounting at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management. “The corporate governance research has shown time and time again that in most instances dual-class shares are just not good in the long term for shareholders.”

Edward Rogers (left), his mother Loretta (centre), and sister, Melinda (Getty)

Edward Rogers (left), his mother Loretta (centre), and sister, Melinda (Getty)

For many years, the rough rule of thumb is that about 30 per cent of family businesses fail in the second generation, another 13 per cent disappear in the third and most of the remainder disappear beneath the waves by the fourth. Those stats frequently find their way into the promotional materials of wealth advisers marketing their services.

Yet, as boomers exit the workforce (or this mortal coil), the question of how to create the right conditions for successful and sustainable succession planning has gained salience. Calgary-based family wealth transition adviser Cindy Radu points to a 2021 report by the Family Enterprise Foundation and KPMG Enterprise, which surveyed hundreds of family businesses and concluded that almost two-thirds expect to change hands within the next ten years. Yet only 47 per cent of the respondents predicted that the business will stay fully in family hands. And, while the vast majority agreed that it’s important to have a transition plan, only half had identified specific family members prepared to take over. “If the owner drops dead tomorrow,” says Barb Schimnowsky, practice leader for executive and director search at Watson Advisers, a Vancouver governance consulting and leadership talent firm, “who’s stepping in?”

Another 2021 survey, by the London, U.K.-based wealth adviser STEP and the TMF Group, canvased over 600 advisers world-wide about the transition challenges they face with wealthy business families and what those families’ wealth and succession planning needs are. The answers included the emergence of more blended “multi-jurisdictional” families and the ways in which these more complicated clans made the internal dynamics around succession that much more complex to navigate.

In many parts of Europe and Asia, family-run business dynasties have far deeper roots than they do in North America. Conglomerates like Tata, the Indian steel maker, and Germany's secretive Reimann family, which acquired Keurig Green Mountain a few years ago for almost $US14 billion, have been passing wealth through the generations since the 19th century. While there’s no shortage of long-established family dynasties in North America, succession planning only emerged in recent decades as a problem that deserved attention. A 1973 Dun & Bradstreet study found that 70 per cent of all family firms were sold or liquidated after the death of the founder. “The lack of succession planning has been identified as one of the most important reasons why many first-generation family firms do not survive their founders,” Ivan Lansberg, a Connecticut-based family wealth adviser, wrote in a heavily cited 1988 wake-up call.

Much has changed since then, of course, as the universe of professionals offering succession advice has expanded beyond trust lawyers and tax accountants to governance, search and philanthropy consultants, family offices, conferences, one-stop wealth advisory practices, and education/advocacy groups established by and for family-owned businesses. Advisers offer hard and soft services, which can include bespoke specialties, such as industrial psychologists summoned to assess whether adult children have the right stuff to take the helm.

"The role of the CPA will vary considerably depending on the number of shareholders, the strength of the management team, and the complexity of the family, the business and the ownership structure," observes Osry. "Regardless of the centrality of their role, it is crucial that CPAs communicate openly with the other advisers and encourage a creative, compassionate and collaborative approach."

Adult children of aging business owners are increasingly versed in the issues related to inheriting a going concern

While the succession planning industry has evolved a great deal, human nature has not. Veterans of the field can rhyme off a full menu of personality-driven failings, among them a natural reluctance within families to discuss the implications of a founder’s death, the endless variations on the problems posed by entrenched family dynamics (e.g., sibling rivalries) and X-factors, such as addiction or mental health issues, or adult children who are driven to take over the business, but have little or no aptitude for running it.

Schimnowsky, who was a senior manager with KPMG’s search practice in Vancouver for 20 years, relates the story of a family where two of three siblings worked in the family business. “One [son] gets moved up into the CEO role,” she explains, noting that he wasn’t ready for the responsibility (a theme in Succession). “All of the other senior management within the organization are external. And, you know, the dad comes in … and makes him feel like a fool. The senior leadership team there are sort of protecting him. And it’s a very abusive relationship [and] actually quite sad to see.”

Watson’s approach, she explains, is to urge the owner to establish a board with independent directors who can, as she puts it, hold the family accountable and advocate for succession planning, skills gap analyses, regular family meetings, good governance practices and the necessary education for offspring. “It’s super important that they learn how to be good owners.” The subject of executive succession, she adds, should be canvassed annually, because the sudden death of the founder can pose huge business risks, such as the loss of key relationships with long-time customers.

Others recommend establishing philanthropic foundations to not only shelter wealth but also build some sense of mission within a business family about shared values and goals. “More and more,” says Osry, “[families] are asking, are we trying to structure ourselves around the wealth and the business? Or are we striving to ensure the strength and well-being of individual family members who will in turn step up to steward the family’s wealth?”

Radu, who practised as both a lawyer and a professional accountant before establishing herself as a family wealth transition adviser, also points out that adult children of aging business owners are increasingly versed in the issues related to inheriting a going concern, as well as the structures that have been set up to hold or pass on wealth. What’s more, she adds, they may not have the same goals as the founders. “The kids are at that age where they're making really important life decisions,” she says. “How does that tie into the values work that we've done with the family?”

For all these softer measures around governance and planning, transition dynamics are often heavily determined by key structural moves that invariably focus on control and mechanisms to ensure that the wealth remains within the family.

Some of these deal with the specific roles of children, such as establishing shareholder agreements designed to ensure that dividends flowing from the growth of the company are distributed equitably between offspring working in the business and those who aren’t. Darren Lund, a partner in Miller Thomson’s private client services group, also adds that owners planning for succession need to consider scenarios like marriages, divorces and second marriages of their children. “Thinking through the family law implications of some of the plans is one piece that sometimes gets overlooked,” he says, noting, for example, that spouses can make claims against a family trust in a divorce proceeding. "It could have a huge impact on a beneficiary or on a business."

The true lesson of the Rogers battle focuses on the way that dual-class shares and family trusts can reverberate through the generations

Wahid, in turn, cites the case of the Desmarais family, whose late patriarch, Paul, acquired a Montreal stock brokerage and built Power Corp. into a multi-billion financial services conglomerate. In the years prior to his death in 2013, he transferred executive and board authority to his two sons, André and Paul, who both retired in 2020. They retain their board seats. Last year, the company undertook a major restructuring that involved taking Power Financial, one of its publicly traded divisions, private. “I believe that part of the reason why they went private,” she explains, “is because they didn’t want to face the pressures that the investors and best practice governance experts were pushing on these companies, saying, ‘well you don't have an independent board, you don't have an independent chair.’”

But, as she and others point out, the true lesson of the Rogers battle focuses on the way that dual-class shares and family trusts can reverberate through the generations, often in unexpected or poorly understood ways.

In the case of Rogers, the combination of dual-class shares and a family trust that controlled the board of directors served to concentrate a huge amount of decision-making authority, including the power to replace the CEO, in the hands of Edward Rogers, who served as the chair of both the Rogers’ board and the family trust.

“One of the biggest issues in the transition of businesses and wealth generally is that people do not understand ownership and the inter-relationship of trusts with their structures,” says Radu. “Rogers was a perfect example of that. Everybody was focused on the board of directors level, but the family trust established by Ted had significant influence over the makeup of the board.”

She contends that many families transferring wealth to the next generation end up with trusts that neither they, nor some of their expert advisers or shareholders, really comprehend. “They put these things in place and the families don’t understand them. They don’t think about it from a governance perspective and where the real decision-making power lies.” Notes Osry: “It is important to not only clarify the legal elements to promote awareness and understanding, but also to be mindful of the emotional connections and psychological implications of a trust.”

“You have to infuse innovation and an entrepreneurial spirit in order to rejuvenate the businesses over time”

Radu adds that in some closely controlled family businesses, these structures can also create conflicting fiduciary roles. She cites the example of an operating company that’s owned by a holding company that is, in turn, controlled by a family trust; the founder or patriarch may have executive roles on all three. “When they start making decisions, it’s usually very tax driven,” she says. “At the end of the year, the accountants will say, ‘Okay, well this is how much we should flow out to achieve a desirable tax result,’ which is a positive thing. But what we’re starting to see in families is family members calling BS on this when it’s only mom and dad [who] are receiving the dividends.”

Robert Nason, an associate professor of strategy and organization and the William Dawson Scholar at McGill University’s Desautels Faculty of Management, has studied succession and the evolution of family businesses across the generations. He points out that the conflict- and lawsuit-generating decisions that delineate many succession plans can miss the mark on a broader point, which has to do with re-invigorating the business itself. He questions the oft-cited family business failure stats, saying they’re derived from a small study that didn't take into account exits such as public offerings. And, he notes, in a technology-fueled economy, family businesses, like all firms, need to find ways of injecting new energy, new products or new ways of generating revenue as they mature and then change hands.

“You have to infuse innovation and an entrepreneurial spirit in order to rejuvenate the businesses over time, or create new firms that are the next entity that will be successful and thrive.” He cites the case of a family-owned Italian steel manufacturer that pivoted to renewable energy when its owner could see that their traditional sector was in decline. Nason notes that some founders will provide the next generation with seed capital so they can test new businesses or technologies and establish their own identities as next-gen entrepreneurs.

“Do we have a one-for-one successor, which pits everyone against each other for this one prestigious spot, [or can we] find a way for all family members to play a role and contribute to an overarching family goal and identity and space?”

As plot lines go, this kind of narrative may be a good deal less engrossing than the intrigue in Succession—or Rogers, for that matter—but it seems likely to foster a more enduring way for founders to transition both wealth and business to the next generation.

ESTATE PLANNING TIPS

Succession planning is critical in business, just as estate planning is essential in your personal life. Read about the ways that taxes will impact the assets you leave behind, and the ways to reduce the tax impact for your heirs.