Meet the inventor of the smartwatch that detects early signs of COVID-19

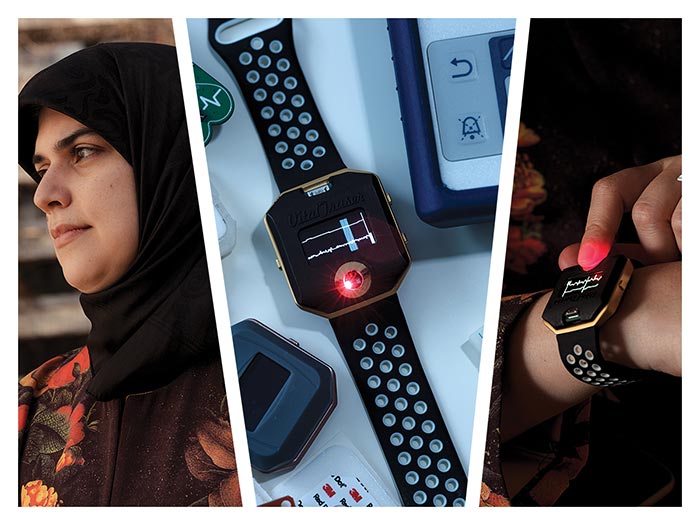

The VTLab smartwatch grew from Azadeh Dastmalchi’s quest to find a monitoring tool for her father (Photography by Alexi Hobbs)

The VTLab smartwatch grew from Azadeh Dastmalchi’s quest to find a monitoring tool for her father (Photography by Alexi Hobbs)

The invention that Azadeh Dastmalchi has focused her research on for the last decade took on a new life in 2020. Her groundbreaking VTLab smartwatch, which provides cardiac monitoring and measures vital signs, is being hailed for its potential to predict and monitor COVID-19.

The smartwatch, produced by her Montreal-based startup, VitalTracer Ltd., tracks vital signs like blood pressure, blood oxygen saturation, body temperature and heart and respiratory rates. It can even track electrocardiogram (ECG) and photoplethysmography (PPG) signals that measure your heart’s electric activity and your body’s blood circulation.

Popular smartwatches like those from Apple, Fitbit and Samsung don’t provide users with the same amount of raw data, claims Dastmalchi, and health care providers are rarely privy to those results. But the VTLab delivers its data directly to doctors or caregivers via Bluetooth or Wi-Fi, and can be viewed on a smartphone and kept in the cloud.

She has accumulated more than a million dollars in research funding to date, with clinical trials set to begin at the ICUs at the McGill University Health Centre and CHU Sainte-Justine hospitals in January. In September, the concept earned her a social entrepreneurship award from the national research organization Mitacs. All of this while the 35-year-old juggles her PhD studies in biomedical engineering at the University of Ottawa.

Dastmalchi’s research supervisor, Hilmi Dajani, a professor in the school’s faculty of engineering, expects she’ll make significant contributions to the field of health monitoring.

“She is not afraid to tackle one of the most challenging problems in biomedical engineering today, namely how to reliably measure vital signs using unobtrusive wearable devices,” he says.

Initial reactions were mixed.

Ten years ago, Dastmalchi vividly recalls her idea being dismissed by an expert she once described her vision to. Though she admits there were tears, they didn’t last long.

“That’s my favourite challenge in my life,” she says from her Nuns’ Island home in Montreal. “If I offer an idea and they don’t believe in me, I try so hard to make it happen.” She recognizes it can be hard to change the perspective of senior researchers who are used to more traditional health care technology. “I don’t expect that they believe in AI technology that looks like a black box performing magic.”

With Dastmalchi’s smartwatch, doctors and caregivers have instant access to patient data

Getting VitalTracer off the ground has proved to be less magic and more an exercise in patience. A few years into her research, a friend with a startup suggested Dastmalchi build her own company because there was a good market for her research focus on hypertension and blood pressure monitoring. But at the time she felt she lacked the business knowledge, so she started taking courses and attending workshops and eventually wrote a business plan. VitalTracer was established in 2016, while Dastmalchi was a full-time PhD candidate. By 2019 she had turned her focus to the company full-time.

The idea for a monitoring product first came about when Dastmalchi was seeking a smartwatch to help her late father, Kazem, monitor his hypertension. But this past year, as she followed news of the horrors COVID-19 was causing in Montreal seniors’ homes, she couldn’t help but think of her father, and wanted to find a way to offer peace of mind to caregivers and patients.

This led her team to research what vital signs and abnormalities could suggest COVID-19. Dastmalchi says the primary indicator is a patient’s blood oxygen level. With continuous monitoring, caregivers can notice if it becomes abnormally low, which is a good reason to administer a COVID-19 test. With Dastmalchi’s smartwatch, doctors and caregivers receive that data in real time, allowing them to act preemptively.

Dastmalchi says the medical industry usually looks at a smartwatch as “a gadget rather than a medical device.” But with COVID-19 wreaking havoc, she’s seen that perception quickly shift. Doctors are exploring ways to provide effective home-care monitoring without direct contact with patients, and she believes her product can help facilitate this shift.

VitalTracer products are in the process of getting regulatory approval from Health Canada and the FDA in the U.S., with the hopes this will be achieved this year. Currently, the VTLab watch is only available for sale to researchers as a minimum viable product (MVP), meaning it’s still in a testing stage and researchers can provide feedback on its development.

“We provide the hardware technology to them so they can build their own software technology based on their own medical architecture,” Dastmalchi says. Apart from monitoring early signs of COVID-19, researchers have expressed interest in using the VTLab to track dementia, sleep apnea and cancer, among other health issues.

Dastmalchi says there are about 700 orders from five different research groups, and aimed for 1,000 by the end of 2020—and to at least double production in 2021.

The pandemic has left Dastmalchi envisioning bigger things for VitalTracer. In a pitch last year, investors referred to her watch as a “vitamin,” but that view has changed. “Now it’s a painkiller,” she says, “and everyone needs it really badly.”

MORE COVID-19 COVERAGE

Read how tech firms are out-boxing Big Pharma in the fight against COVID-19 and how developers are refining sprays, barriers, and even fabrics designed to kill viral germs on contact.