Can a 3D architectural printer be the housing solution we need?

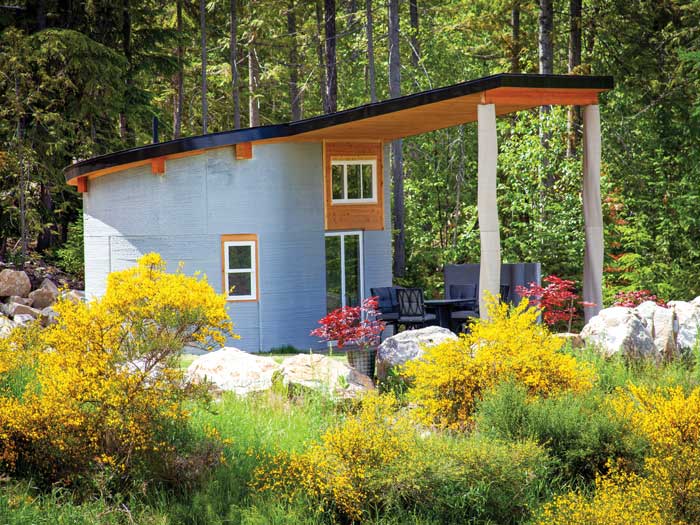

The 3D-printed Fibonacci House in Procter, B.C., can be rented via Airbnb (Courtesy of Twente Additive Manufacturing)

The 3D-printed Fibonacci House in Procter, B.C., can be rented via Airbnb (Courtesy of Twente Additive Manufacturing)

When Ian Comishin, from Kimberley, B.C., launched a 3D printing company in the Netherlands with four other partners in 2018, the idea was to build 3D architectural printers, with the goal of building 3D-printed homes. “We had no idea what kind of tiger we were grabbing by the tail,” Comishin says.

They emerged with Canada’s first 3D-printed home, the Fibonacci House, a small structure of about 400 square feet in the scenic community of Procter, B.C. The home, built in 2020 and made rentable on Airbnb last summer, serves as a blueprint for future 3D developments in this country.

As Canada continues to experience a housing affordability crisis, Comishin’s company, Twente Additive Manufacturing (TAM), sees 3D printing as a viable solution. With outposts in Europe, Dubai and Canada, TAM is continuing its work of developing 3D architectural printers for a growing global client base. According to Comishin, 3D-printed homes are a more affordable, quick-to-build alternative to traditional construction methods and can help solve housing shortages in communities across the world.

While the technology is still in its infancy, the process is relatively straightforward: TAM’s 3D printers push out a special concrete mix through a nozzle (like toothpaste squeezed from the tube), creating layers of concrete to construct a wall. This method is indeed time-effective—TAM’s first 3D-printed house was designed, printed and installed in five weeks—and cheaper than conventional means. Comishin says, at this stage, it’s 15 to 25 per cent cheaper to construct a 3D home.

The time factor is a major selling point. So far, TAM is working with international organizations to house people experiencing homelessness or folks priced out of the market. One such initiative is underway with the Vancouver-based charity World Housing to build an “affordable village” of five two-bedroom homes for families in need in Nelson, B.C. TAM has also teamed up with the University of Windsor and Habitat for Humanity to build residential homes in Windsor-Essex, Ont., a project that is slated to be completed in the coming months.

TAM has engineering and administration wings in the Netherlands, but the firm also has a subsidiary in Dubai, a research and development facility in Germany and two operations in B.C. It currently produces its printers in Hemmingford, Que. Comishin says there’s been high demand globally for 3D printers like TAM’s, with similar affordable housing projects being planned in Japan, the Middle East and South America.

TAM develops sophisticated 3D printers to be sold and also offers 3D printing services. This means the company is constantly engaged with its own product line and can evolve technologies rapidly. Printers and printing services are TAM’s two main revenue generators, however, Comishin says engineering, consulting and software licensing all contribute to its bottom line.

Nemkumar Banthia, a professor of civil engineering and Canada Research Chair at the University of British Columbia, believes 3D printing technology holds potential when it comes to housing, and says it can also promote sustainability. Through streamlined robotics and IT, construction waste is cut by 30 per cent in the production process, he estimates. A 3D printer can be used over and over again, and designs can be modified by updating the software instructions that tell the printers what to do. And, because the software can be easily updated, it allows for more architectural freedom to customize homes. “Moreover,” Banthia adds, “3D-printed homes are more suitable for some emergency situations, like resettling [communities] after a catastrophe.”

In the U.S., Scott Dunham, vice-president of research at the 3D printing market research firm SmarTech Analysis, believes that, despite the relative speed in which they are constructed, typical barriers remain.

“It has some inherent challenges, because most 3D structures require a staged approach so utilities and such can be integrated into the structure,” Dunham explains. This means that even if a printer can quickly produce concrete walls, a home still needs tradespeople to install electricity, plumbing and insulation.

Skilled workers must be trained to design the structures and operate the machinery, and this is one area in which Comishin feels Canada may be falling behind. “All over Europe, there are technical universities teaching the software and hardware behind this technology,” he says. “Canada needs to catch up.” In Nelson, Selkirk College quickly adapted its digital manufacturing program at its Trail, B.C., campus to study 3D-printed homes and TAM’s methodology. “They bring their students out to our R&D lab and we let them design parts that we will print for them so they can get a feel for the capabilities of the technology.”

Banthia says 3D printing is the future of sustainable and affordable housing across the globe, including in countries such as China, the U.S. and Singapore, where entire neighbourhoods have already been built using the technology. 3D printing activities will reach an estimated global value of US$55.8 billion by 2027.

HOUSING AND SUSTAINABILITY

Canada’s housing market may be slowing down in certain markets but it still broke records as prices soared and supply dwindled. Read more about this impact. Plus, find out what Canadian who don’t own homes feel about their chances of entering the housing market with this recent CPA Canada survey.