Why at-home testing is the next frontier in DIY lab work

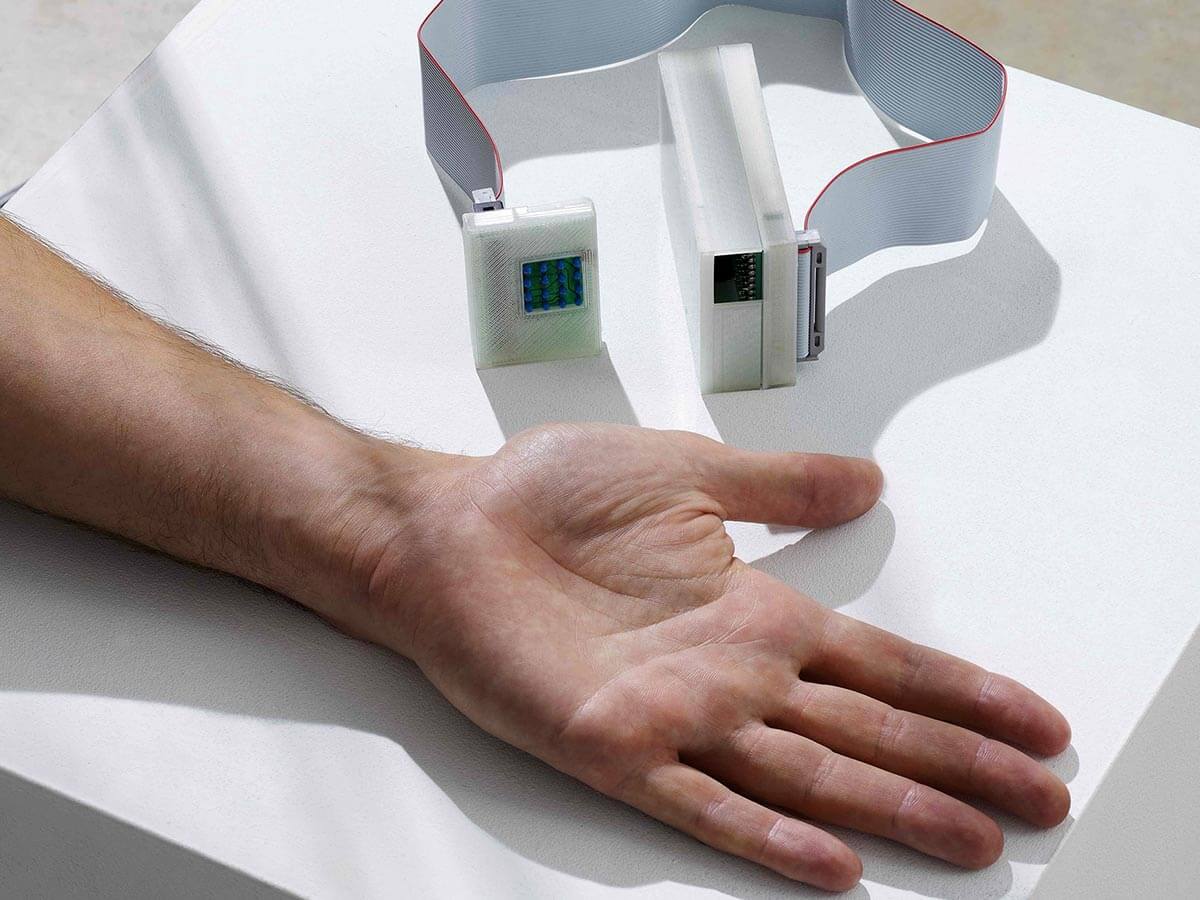

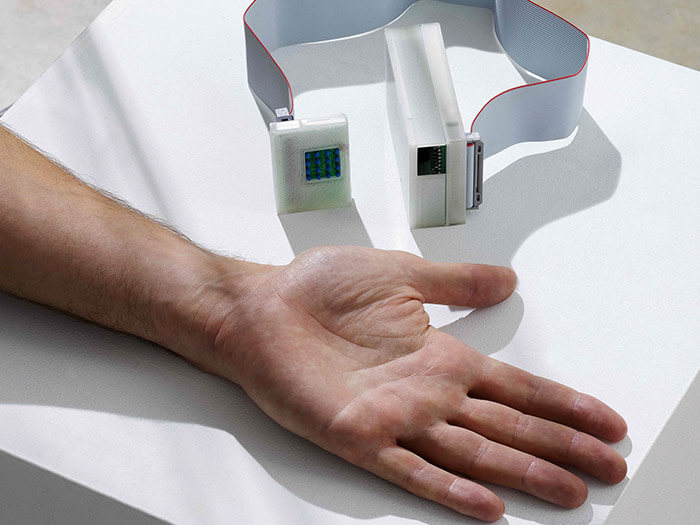

Skan, the hand-held heat sensor used to detect melanoma (Photograph Courtesy of Dyson Canada)

Skan, the hand-held heat sensor used to detect melanoma (Photograph Courtesy of Dyson Canada)

Every year since 2007, James Dyson, the British billionaire who got rich engineering sleek, bagless vacuums, awards a prize to a design he thinks will solve an important problem.

For two of the last four years, Dyson has selected portable, easy-to-use cancer diagnostics. In 2017, the award went to the Skan, a device used to detect melanoma using an inexpensive, hand-held heat sensor devised by a Canadian team from McMaster University. Most recently, Dyson selected a breast cancer test developed in Spain called the Blue Box, where urine deposited into a small vessel is analyzed via a smartphone app. While neither product is currently commercially available, both could be game-changing in the time of COVID-19.

According to a 2020 study by Canada Health Infoway, a non-profit organization specializing in digital health care, prior to the pandemic fewer than five per cent of doctor visits took place via phone, video, text or app. After the start of the pandemic, that number jumped to 60 per cent.

As patients avoided in-person medical visits and hospitals re-prioritized to fight COVID-19, cancer testing across Canada declined throughout the first year of the pandemic. In Ontario, mammograms dropped by 97 per cent between March and May 2020, according to Ontario Health. In Alberta and B.C., tests of all cancers decreased by up to 25 per cent between March and September, according to the respective provincial health agencies. Although testing became more regular again by late 2020, it never returned to 2019 levels, leading to concerns that undetected cancers might soon devastate unsuspecting patients.

At-home tests, like Blue Box, could not only cover the testing gap, they might also help lower the cost of diagnostics. (Blue Box is expected to cost about $60; a traditional mammogram costs the province more than $240.)

“Before COVID-19, there was an under-investment in virtual and digital health care delivery,” says Mary Sanagan, a Deloitte consulting partner specializing in medical technology. “However, the pandemic has inspired a lot of innovation and investment. I’m optimistic this could all lead to better, more patient-centred care.”

Aiden Poole, an Alberta-based CPA who consults with medical and technology companies, cautions that there are challenges when it comes to bringing new health tech to market in Canada. “In terms of business development, I typically see two to three years of hardship for health care startups,” he says, citing high capital costs and the difficulty of finding a clinic willing to test new products as the main challenges. But he also shares Sanagan’s optimism. “A startup with a fresh idea that makes an assessment between doctor and patient easier for both parties will be successful in today’s market,” says Poole.

It helps that the market is being spurred by big investments: The federal government has committed $240 million to expand online health care.

Some clinicians believe there are innovations hiding in plain sight. Dr. Mohammad Akbari, a research scientist at Women’s College Hospital in Toronto, is advocating for more people to have access to at-home genetics sampling collection to see if they have a predisposition to various cancers. “The lifetime risk of a woman to be diagnosed with breast cancer here in Canada is about 10 to 12 per cent,” he says. “However, somebody carrying certain genetic mutations, like the BRCA mutation, might have risks between 60 or even 80 [per cent]. The earlier someone understands the risks, the earlier they can understand their options in terms of prevention. And, in general, prevention is less costly than treatment.”

Yet genetic testing is tricky to obtain and an expensive process. While Akbari waits for that to change, he is running a program through Women’s College Hospital called the Screen Project, which offers at-home tests and is available to anyone over the age of 18.

The tests cost US$250, out-of-pocket to the patient. The Screen Project first launched in 2017 to study the feasibility of population-based genetic testing for breast cancer markers, then relaunched in 2020 to cover other cancers such as ovarian and prostate. There have been over 3,000 participants in the original study, resulting in 1,269 tests taken. “I wish it were more,” Akbari says, “but all the money goes to the lab. We have no budget to advertise.”

Brampton, Ont.-based Dynacare also offers genetic testing for cancer: a mail-in stool sample that screens for colon cancer.

Elizabeth Holmes, senior manager of policy and surveillance at the Canadian Cancer Society, notes that test results don’t provide a diagnosis; no one gets a slip of mail reading, “You have cancer.” “If someone has warning signs, they are alerted to see their doctor,” she says.

“It doesn’t cut out the medical system. What it does is cut down on the number of people who might be walking around unaware.”

LEARN MORE

Here’s what you need to know about about PGx, the DNA test that can predict your reaction to certain medications and read how injectable technology will allow you to open doors and log into websites with a wave of your hand.