We use screens for 11 hours a day. At what cost?

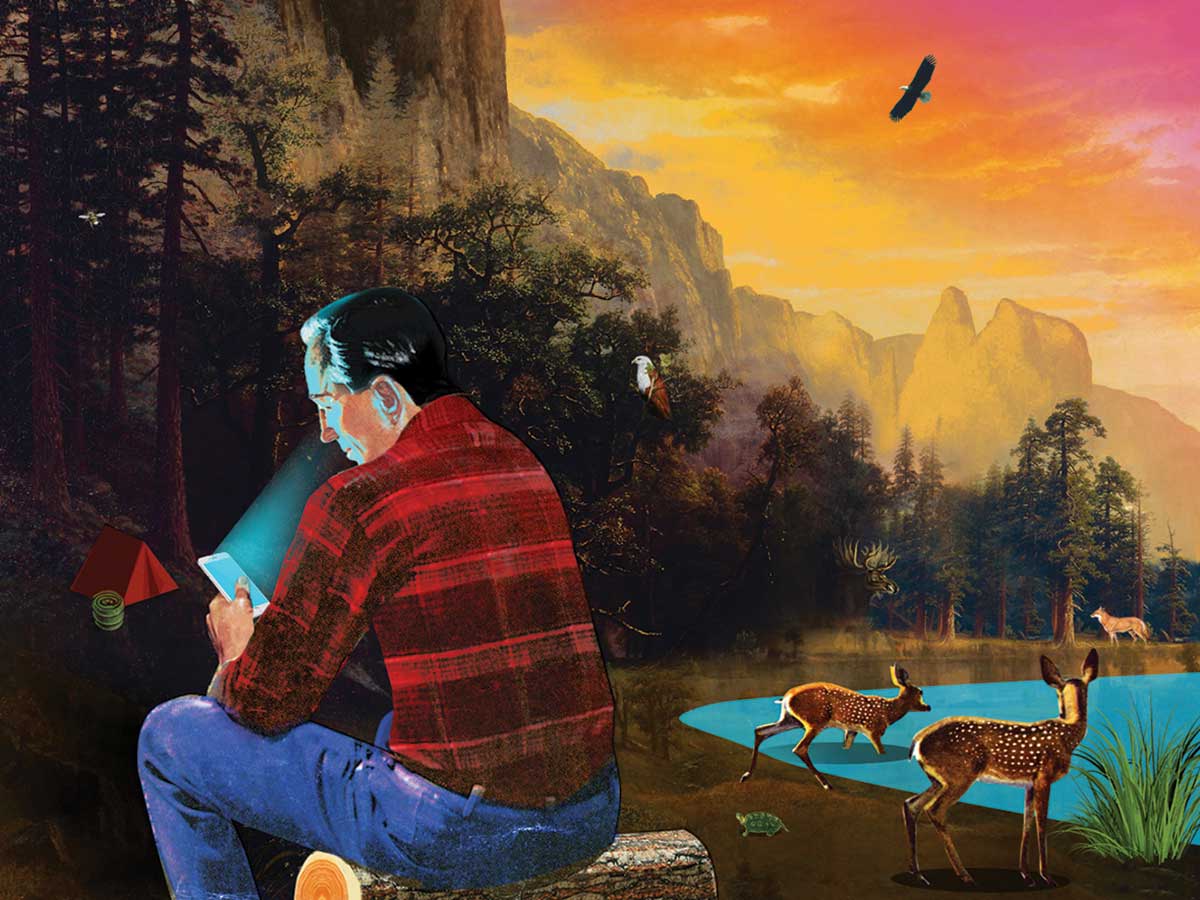

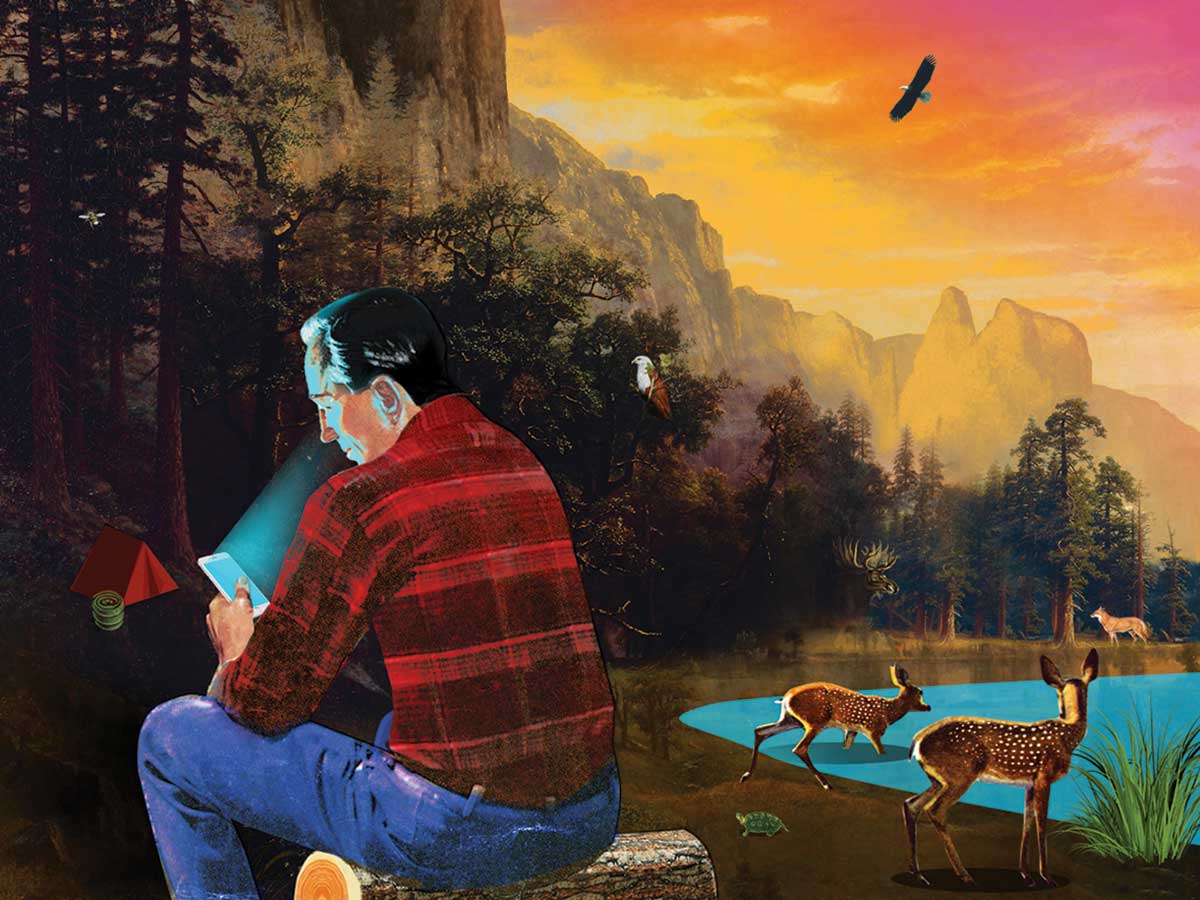

Screen time has been linked to increased levels of obesity and it’s making more of us mildly and severely depressed. (Illustration by Matthew Billington)

Screen time has been linked to increased levels of obesity and it’s making more of us mildly and severely depressed. (Illustration by Matthew Billington)

Two months ago, I sat in a tent pitched 6,000 feet up in Yosemite National Park’s remote wilderness. I’d just hiked six hours up into the Sierras to breathe the crisp air, bathe in a waterfall and fall asleep under the summits of Half Dome and Clouds Rest. My friends and I had cooked dinner over a palm-sized stove and warmed ourselves at a campfire. All that was left to do was fall asleep to the sound of rustling leaves. I’d been dreaming of this moment for months, a serene vacation under a blanket of stars. And yet, I found myself reaching for my phone, bargaining with myself. What if I’d missed something important since yesterday? I swept my thumb across the slider to take it off airplane mode. Even high up in the alpine backcountry of one of the world’s most incredible vistas, I couldn’t resist checking my email, responding to a note from a client and taking a casual stroll through Instagram.

It turns out that I’m far from alone in that impulse. Last year, the market research firm Nielsen found that American adults were using screens an average of 11 hours per day. In front of the TV, which made up more than four of those hours, 45 per cent of those watchers were often or always using two screens at once—watching while scrolling through their phones or tablets. According to Apple, the average iPhone user unlocks their phone 80 times a day, which, accounting for eight hours of sleep, means once every 12 minutes for 16 hours a day, every day.

Most of the research that’s been done on screen time and health looks at children or teens and their brains-in-development. But how harmful is screen time for adults, who are increasingly tethered to screens at work as well as at home? According to researchers, it’s pretty bad. This past March, a group of social and data scientists from Stanford, Penn State and Boston universities argued that the very concept of “screen time” was no longer relevant or effective. Screens had become so pervasive, they said, that we needed to look at an individual’s “screenome” for insight into how we’re using our devices.

The average person unlocks their iPhone 80 times a day. That’s once every 12 minutes for 16 hours, every day.

To get this personalized sequence of data, researchers installed software on participants’ laptops and phones that took screenshots every five seconds, drilling deep into the details to create a comprehensive picture of what we’re looking at and how we’re spending our time. The findings were illuminating: most people rarely spend more than 20 uninterrupted minutes on a single activity, switching from one to the next an average of every 20 seconds, in an infinite loop of distraction.

It turns out biochemistry is working against us. Our brains are wired to want to check in. App developers are employing behavioural scientists to make their products as addictive as possible. And nomophobia—the fear of being without your phone—is increasingly being studied by behavioural scientists and the psychology community as a condition. “Every time a notification buzzes or beeps, the brain releases chemicals that signal anxiety,” says Larry Rosen, psychology professor emeritus at California State University Dominguez Hills and co-author of The Distracted Mind. “That leaves us on the alert too many times during the day, and even during the night.”

Too much screen time is also decimating our eyesight: 59 per cent of American adults report experiencing symptoms of digital eye strain—physical discomfort such as headaches or blurred vision after two or more hours of screen use. Screen time has been linked to increased levels of obesity. It’s making more of us mildly and severely depressed. It’s causing our grey matter to atrophy and our executive functioning to falter. It’s more likely to cause insomnia, which in turn has been linked to job loss. And while it hasn’t been proven that increased screen time necessarily causes health problems, several studies have shown alarming correlations: one study found that more time spent in front of screens was associated with type 2 diabetes in adults. Another linked excessive leisure screen time to an increased likelihood of cancer and heart disease.

If all of this has you running for the hills—without your iPhone, camera or any other screen—take heart. As Rosen says, not all screen time is created equal, and features like Screen Time for iPhone users or apps like Digital Wellbeing for Android can be useful in correcting for wasted time. Rosen suggests implementing tech breaks—removing any unneeded websites and apps from screens—and setting an alarm for 15 or 30 minutes, depending on how distractible you are. When the alarm goes off, you’re free to use your personal tech for one or two minutes. “Once that starts to feel easy,” he says, “then increase the focus time to a point that feels right.”

Too much screen time is also decimating our eyesight: 59 per cent of American adults report experiencing symptoms of digital eye strain.

Employees on laptops or desktops might try a gadget like TimeFlip, a “productivity polygon,” which you flip every time you start a new workday activity, from analyzing spreadsheets to answering emails. A small plastic device that can be folded into a six-, eight- or 12-sided polygon, the TimeFlip sits on the corner of your desk and links up to a smartphone, registering each time you flip to a new side and tracking how long you’re spending on each task. The idea is to effectively manage your screen-based work so you can leave more time for discussions over coffee and a notepad, or walking meetings through the park.

Three years ago, workaholism in France reached such a fever pitch that lawmakers passed a bill granting citizens the “right to disconnect” from work emails outside of office hours. They mandated that companies larger than 50 people negotiate after-hours email rules with employees. Such legislation may be difficult to enforce: in one academic study of the bill’s impact, published almost two years after it went into effect, 97 per cent of the survey participants declared that they had not seen any relevant changes since the policy was implemented in January 2017. But the study’s results also showed that more and more people had become aware of the problem and were taking steps to cut down on their after-hours connectivity. And in Canada, a yearlong consultation on changes to the federal labour code found that 93 per cent of respondents believe employees should have the right to wait until office hours begin to respond to work-related emails.

It won’t help decrease screen time spent at work, but Canadian employers would do well to take note. After all, in resisting the urge to reach for a screen, our brains need all the help they can get.